“Social Mirror has made a massive impact in my life because when I moved here I had nobody and nothing. Going to groups through Social Mirror started the ball rolling….”

In my time at the Connected Communities team, ‘social networks’ have gone from ‘huh?!’ to buzzword by way of Facebook and Twitter. This is a good thing. Feeling supported, connected, needed and part of a community is essential to doing well and to be able to turn your aspirations and ideas into reality.

However, what is missing is a concrete sense of the theory of change behind a networks approach: amongst all these calls to set up time-banks and end loneliness, what does a social networks-based approach look like, if you look it in the eye?

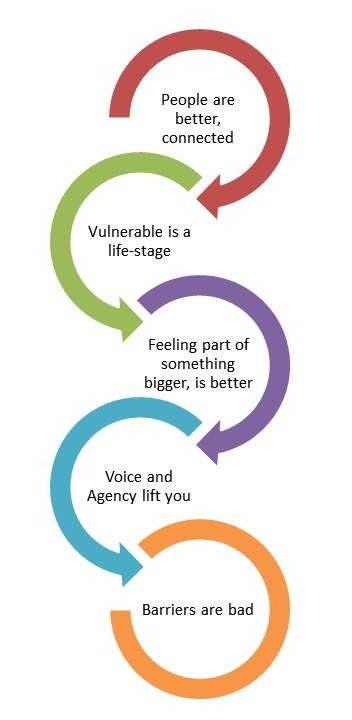

I will be outlining Five rules, Four principles, Three approaches, Two caveats and One request.

Five Rules:

Here in the Connected Communities team, we have done a lot of work on how people’s connections influence their life outcomes, how they feel, and their ability to turn their ideas into reality. These rules are a further iteration of my earlier ‘five community questions’. I hope they will be of interest and use to anyone who does voluntary or community work, or for anyone working for or with organisations that work with people and/or communities at a local level.

Here in the Connected Communities team, we have done a lot of work on how people’s connections influence their life outcomes, how they feel, and their ability to turn their ideas into reality. These rules are a further iteration of my earlier ‘five community questions’. I hope they will be of interest and use to anyone who does voluntary or community work, or for anyone working for or with organisations that work with people and/or communities at a local level.

-

People are better, connected.

Our work to date has highlighted the importance of feeling connected and supported across the board. We surveyed 3000 people in seven areas to assess the impact of social and community inclusion on mental wellbeing. We found that people who do not have others they feel close to, tend towards reporting lower feelings of meaningfulness in their lives; those who do not have ready access to practical help, such as help around the house or picking something up from the shops, tend towards reporting lower life satisfaction.

You may not feel this applies to you. The RSA-supported Talk to Me London project sparked quite the Guardianista backlash – “Talk to people, in LONDON?!” However our findings show that on average, being locally supported has a marked effect on doing well. Trusting people locally and feeling like your local community is friendly are well-used markers of social cohesion. Maybe having a natter with your neighbours may be more important than you think.

A local pastor in New Cross, London, highlighted that it was the middle classes who were often at risk of low wellbeing in his parish: many of the problems he comes across involve the ‘incomers’ – middle class, new(ish!) arrivals who buy/rent in the area but have family roots elsewhere and work in central London – when these people lose their jobs or have a personal crisis they don’t have a local support network and become isolated.

-

Vulnerability is a life-stage, and it changes depending on where you live.

Wellbeing depends on where you live and what life-stage you are at. People can be vulnerable in ways that are area –specific, and different groups of people are vulnerable at different stages in their lives, such as when being unemployed, having a long-term illness, raising children (especially as a single parent), or after retirement.

These interactions between area and life-stage will not always be obvious to outsiders: contrary to all national trends, we found that in the L8 postcode area of Liverpool – at the time, an area of 40% unemployment – those with qualifications at A-level and above had lower life satisfaction than those who were less qualified. In Tipton, Midlands, we found that the unemployed with higher qualifications faired far worse than the unemployed with no qualifications. Whilst single parents in New Cross tended towards higher than average life satisfaction, we found that in the village of Murton, County Durham, single parents had far lower life satisfaction and mental wellbeing.

My hunch is these differences all boil down to what you were led to believe your life would be, and about what you think is ‘normal’. In an area where it is ‘normal’ to be unemployed, being highly qualified may actually lead to lower life satisfaction. You might feel stuck and like you are fighting a losing battle: this was not the local economy that your education had led you to expect.

Similarly, our findings about single parents in Murton came as no surprise to a project partner who, coincidently, was originally from the Murton area but now lived in New Cross: she explained that in the village she was from, being a single parent was hard, and a real source of stigma. In New Cross, being a single parent is relatively ‘normal’ and there is a lot of support out there.

Indeed, for the majority of these groups, social support acted as a ‘buffer’ to the low life satisfaction and wellbeing scores they were otherwise likely to experience. In Murton, Durham, the more community and social connections single parents had, the better their life satisfaction. In New Cross, whilst generally doing well, both single parents and those of the age of 65 did very badly if they did not have any social support.

-

Feeling part of something bigger than you, is better for you.

Our research in Blackburn highlighted that those who ‘feel part of something that [they] would call a community’ had higher life satisfaction, mental wellbeing, area and health satisfaction, as well as reporting better levels of social support. This is further bolstered by our mental wellbeing and social inclusion work, above, where we found that having aspirations that lined up with and were supported by your local area was fundamental for you wellbeing and life satisfaction.

We are further developing our research in this area in all the evaluations of projects piloted as part of our mental wellbeing and social inclusion programme: for example, in our evaluation of the digital social prescribing ‘Social Mirror’ pilot, we have found Social Mirror increased a feeling of knowing what is happening in the local area for every 6 people in 10 users (62%), and increased their feeling of feeling part of the community for 3 out of 10 users (32%) – nobody reported negative effects (phew!)

-

Everyone needs a voice and access to their own Agency

As a rule, having access to those in authority or who can get things done locally is very good for you. Being ‘known’ locally tends to be associated with higher wellbeing and life satisfaction scores. However this ‘voice’ needs to be meaningful: it is accepted that feelings of control and ‘efficacy’ are a fundamental component of good mental wellbeing. Consultation without action can damage both the wellbeing and local trust of residents.

Our work highlighted that those who were connected to local power holders without having access to social support actually had lower life satisfaction across the board. It is not enough to know that you could go to your councillor, or to know so-and-so at the police: you need the support system around you to make use of these useful connections.

-

Barriers are bad.

One of the most common links between wellbeing and social connections in our research was the link between lower life satisfaction and either feeling that there were things that stopped you feeling part of the local community or identifying places you tried to avoid.

These means that is important to listen to complaints: it does not matter if it is litter, or an annoying neighbour or poor transport links that are blocking you: any blocker is bad and should be taken seriously.

If you found this interesting, stay tuned for my Four principles, Three approaches, Two caveats and One request!

Gaia Marcus is a Senior Researcher on the RSA Connected Communities project.

She is an Edgeryder and an UnMonk advisor, founded the RSA Social Mirror project and is ¼ of the ThoughtMenu.

This Summer she will be cycling 1000km in memory of our RSA colleague Dr Emma Lindley and

You can find her on twitter @la_gaia

Be the first to write a comment

Please login to post a comment or reply.

Don't have an account? Click here to register.