The state is on the retreat. George Osborne recently called for suggestions from public services on how to save £20bn in the autumn spending review. Between the start of the coalition government in 2010 to the end of the new one in 2020, on current projections spending on public services, administration and grants by central government is projected to fall from 21.2 per cent to 12.6 per cent of GDP. Clearly such huge changes in the spending of the state will draw up a new relationship between government and citizen, a new deal on what is expected from the state.

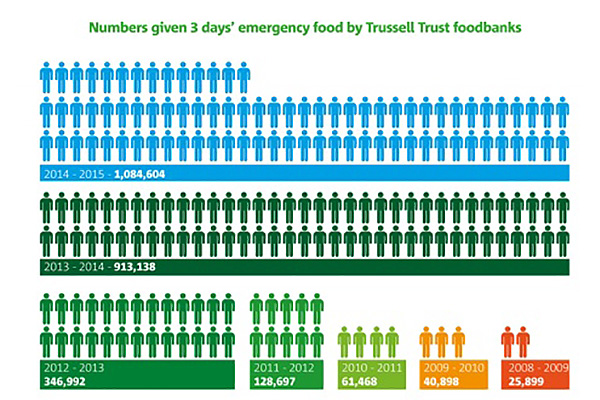

But what are the consequences of this shift? Food banks are on the front line of this redrawn boundary, with charities, schools and other services plugging a void which the state once filled. The UK’s Faculty of Public Health stated that “the welfare system is increasingly failing to provide a robust last line of defence against hunger.” It has been well reported that there has been a huge rise in the use of food banks in the UK. Back in 2012 I carried out a snapshot piece of research on the state of food banks in Hampshire, when the Trussell trust network of food banks was supporting 128,000 people across the UK with enough food for 3 days. Since then it has exploded to over a million (read this article for an over view of how the Trussell Trust figures work).

Source: Trussell Trust

Food banks provide emergency packages of food for people in crisis, usually enough food for 3 days after being referred by a doctor, social worker or job centre. We must be clear that food banks deal with the symptoms of poverty, not the causes. While many food banks do make an effort to signpost their clients to other support agencies which can address these underlying causes; there is a potential issue that with food banks’ increased presence, their services will be seen as a replacement for more long term solutions. They are a crisis support, not a replacement for addressing people’s underlying needs, so with increasing food bank use what is the crisis going on in our social support system?

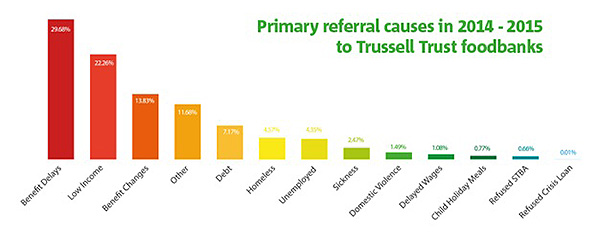

Food banks are a barometer of social change, they are on the front line of a failing social security system. How can we account for the reasons people are being pushed into food poverty? The top three reasons people visited food banks reported by the Trussell Trust are benefit delays (including sanctions, problems with Employment Support Allowance or missing tax credits), low income and benefit changes making up almost 70% of people’s reasons for using a food bank.

From 2012 the introduction of tougher sanction rules following the Welfare Reform Act 2012 saw a massive increase in the number of sanctions imposed on job seeker claimants and those on employment support allowance, from an average of 35,500 a month before the changes to 84,400 a month after. The British Medical journals’ analysis found an association between spending cuts, benefit sanctions and unemployment and the number of food banks in an area. The stripping back of the state has left the vulnerable exposed, with communities plugging the gap.

Sanctions are having a real impact on those who have complex needs and are already in danger of not coping, pushing them over the edge into food poverty. A Report found that the gaps in the social security safety net are causing people to go to food banks when other coping strategies fail. We must admire the amazing work of food banks and their volunteers who are making a massive impact in local communities. These communities are pushing to alleviate poverty and are a strong reminder that where the state begins to fail, communities will step up. The growth of the Trussell Trust network of foodbanks has been an amazing reaction by the voluntary sector and demonstrates the massive altruistic capacity that lies within our communities.

Despite the amazing mobilization of community support, we must question some of the implications of this change from state led public services to more civic responses to alleviating food poverty. As my colleague Atif Shafique recently argued the changing relationship between citizen and state risks fuelling social inequalities within Britain.

The main issue is access. While bottom up initiatives are the best solution to meet local need, they are arbitrary in provision. Social exclusion is a very real issue when local services are dependent on the philanthropy of local communities. This is a particular issue in affluent areas where there is no perceived need for food banks by local residents and where broad brush statistics often mask deprivation. This became clear to me in Hart, Hampshire, which is one of the most affluent and was recently voted the most desirable area to live in the UK for the third year running. Interviewing at the Hart food bank, it was clear that local people often didn’t see a need for a food bank there; meaning local people who needed help faced the double whammy of being in crisis with increased stigma.

In 2012, I mapped food bank provision across Hampshire and found that food banks are much less common in rural communities. While it is expected that provision is sparsest in rural and affluent areas where demand is lower, there is clear need in these areas and these are the groups of people who miss out. But others miss out too, there are concerns that food banks can be inaccessible for the elderly who are often the most reluctant to ask for help. It should also be remembered that access to food banks is often controlled by referral agencies and can vary depending on staff’s willingness to refer. For these reasons current food bank provision is unlikely to meet demand, for they can only fill the gap ‘patchily and partially’.

As well as patchy provision, the third sector is often value driven and in the case of many food banks is driven by faith. The Christian ethos is a real strength of the Trussell Trust network drawing on a large pool of willing volunteers and donators, as well as Churches being the premises where many food banks are located. Although the intention is to be fully inclusive, the possible implications of faith within support services should be considered. The Trussell Trust is quite clear that its food banks should not put themselves in a position where acceptance of public money would limit their expression of their Christian ethos. This raises an interesting tension with food banks becoming increasingly ‘institutionalised’, by this I mean an increasingly established and legitimate part of our social security system.

The work of food banks is an amazing life line for people who are often facing a back drop of ‘ill health, bereavement, relationship breakdown, substantial caring responsibilities or job loss’. However, they are a crisis support which is no replacement for services which address the underlying causes of food poverty such as housing issues or unemployment. While the welfare system has provided a safety net for citizens going through a period of crisis in the past, recent changes mean it is no longer sufficient to stop people entering food poverty. Over two thirds of people in the recent Emergency use only report cited problems with the benefits system as the reason for their immediate income crisis. Food banks do make a difference, yet patchy provision, faith issues and accessibility mean that some people are missing out. The line between state and citizen is being redrawn in the sand; we are just starting to see the consequences.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.