This week the RSA publishes a new report that attempts to make sense of makerspaces – why they are emerging, what impact they are having on their users and communities, and what challenges they are likely to face in the future. Here we present 8 key findings from our research, which includes a survey conducted by YouGov.

From 3d printing to pottery, and from eco-retrofit classes to Arduino bootcamps, a social movement has emerged based on making and mending. People are learning new skills, creating new enterprises and enjoying the satisfaction of mastering technology and craftsmanship. But this is more than just a rediscovery of craft married to 21st Century technology – this is about a collective approach to mastering technology together. It is as much about being as making.

#1 – Across the country, people are coming together in makerspaces to create, fix and modify objects

Makerspaces are open access workshops hosting a variety of tools – from laser cutters and sewing machines through to soldering irons and woodwork devices. They vary considerably in their make-up, objectives, business models and membership base. Makerversity in London is dedicated to supporting maker start-ups, while MakLab in Glasgow has a strong bent towards education and skills development. Nesta estimates there are close to 100 up and running in the UK, and that the pace of their expansion is increasing. Universities, libraries, local authorities, central government and big business have all shown an interest in supporting their development.

#2 – The emergence of makerspaces reflects a nation increasingly enthusiastic about making

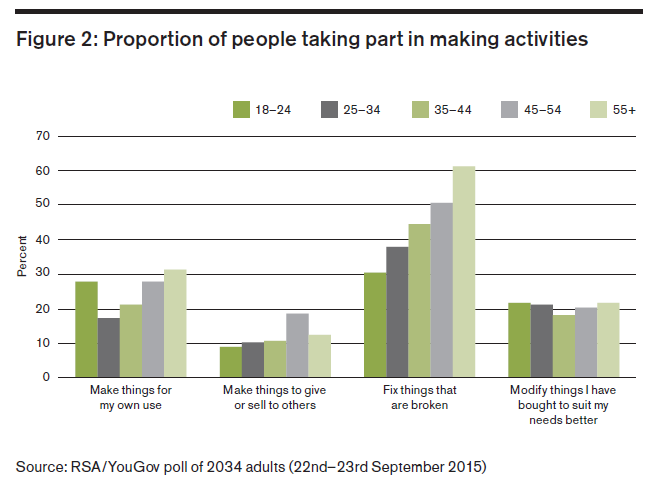

Makerspaces are the epicentre for the wider maker movement. Broadly speaking, this movement champions individual acts of making as both intrinsically worthwhile and beneficial to our society and economy. A recent poll we conducted in partnership with YouGov found that a quarter of people make things for their own use, half fix things that are broken and a fifth modify products to better suit their own needs. We also found that 57 percent of people would like to learn how to make more things that they are their families could use.

#3 – It is useful to examine the rise of makerspaces through the lens of technological change

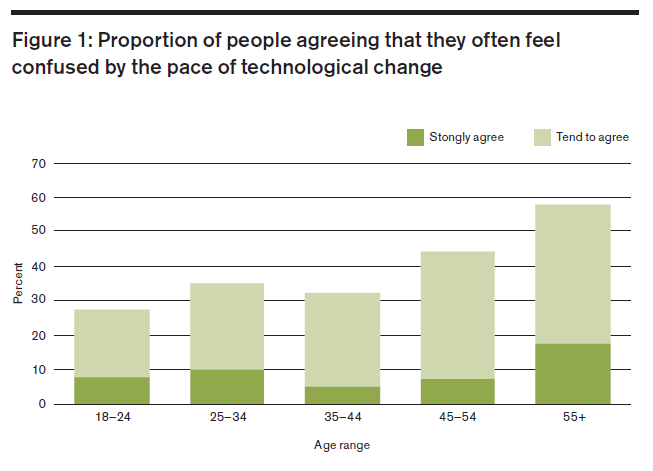

One explanation for the growth of makerspaces is that making has been caught up in the cycles of fashion. Another says the source lies in stagnating wages, with people being forced to make and repair objects they would otherwise have bought brand new. Both these observations contain elements of truth, but we propose a more profound hypothesis: that the maker movement is a reaction to significant technological upheaval and indicative of a desire among people to have more control over their lives – as workers, consumers and citizens. The act of making is one means of regaining mastery over technology – not just because it enables us to be more self-reliant but also because it can boost our sense of agency.

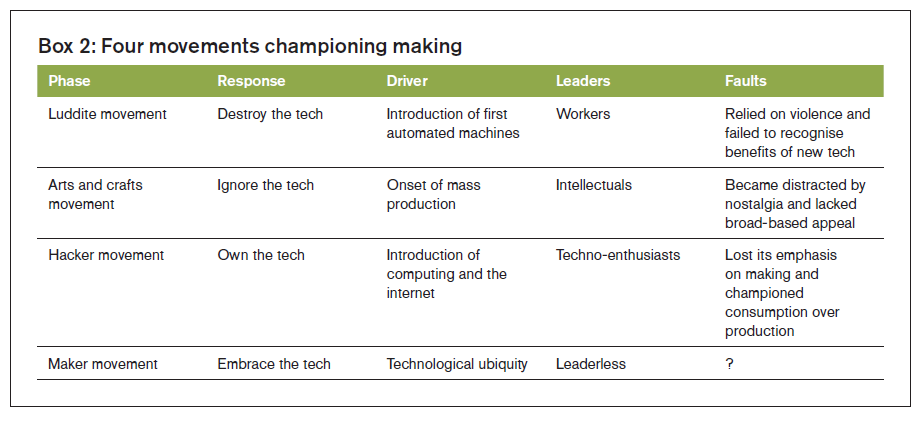

#4 – The maker movement is clearly distinct from the arts and crafts movement

It is tempting to draw comparisons between the maker movement and the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century, which promoted hand-crafted objects at a time when mass production was taking root. But what sets the former apart is that it has chosen to embrace new tools rather than shun them. Although its objectives were admirable, the Arts and Crafts movement was overzealous in its dislike of new machines and became distracted by nostalgia. We should also recognise that the maker movement stands apart because of its conduct. It is highly inclusive, meaning there is a strong feeling that everyone should be able to take part in making. It is also agenda-less, in that every individual is able to choose what they want to work on free of judgement from others.

#5 – Makerspaces can help us master technology for three ends: self-fulfilment, learning and enterprise

What does technological mastery mean in practice? In our report we suggest that makerspaces can help people to use and understand tools for three key purposes:

- Self-fulfilment – Making has been shown to have therapeutic and physiological benefits. But equally important is the impact it can have on people’s self-efficacy. Creating, fixing and modifying objects gives people a feeling of responsibility and control they may be lacking within their daily lives.

- Learning – The vast majority of makerspaces host classes for their users, either for free or at a nominal cost. There are introductions to 3D printing, bootcamps for Arduino, masterclasses in throwing clay and even classes in so-called ‘mind hacking’. It is common for makerspace members to find employment as a result of the skills they have picked up on site.

- Enterprise - Makerspaces can help people turn their ideas into marketable products and in doing so establish viable maker businesses. During our visits, we heard of surgical equipment producers, boat repair technicians and camera designers – all of which had used makerspaces to rapidly and cost-effectively create prototypes of products.

#6 – But makerspaces should also be seen as sites of agitation that champion a different way of living

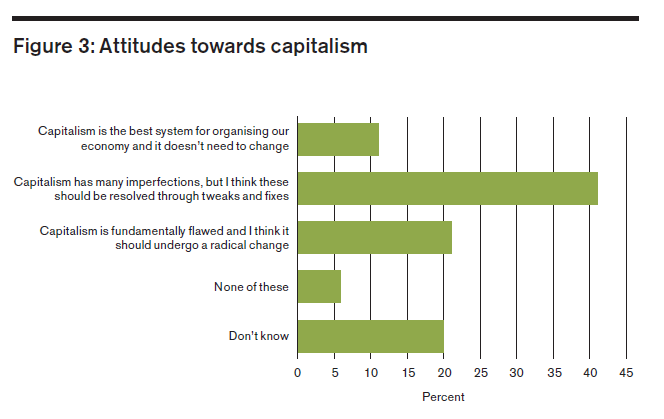

Makerspaces are not just sites to craft objects but also places to champion values and experiment with a different way of living – one that may be based on the virtues of self-reliance, sustainability, data agency and open source knowledge sharing. Fab Lab Barcelona runs a Smart Citizens initiative that encourages residents to monitor local levels of noise and air pollution, MadLab in Manchester organises workshops teaching people how to eco-retrofit their homes, and the ZB45 makerspace in Amsterdam hosts monthly gatherings for people to talk about technology and its impact on censorship and surveillance. All this comes at a time when people are beginning to question the principles of capitalism and look for alternative ways of organising our economy and society – as revealed in our survey.

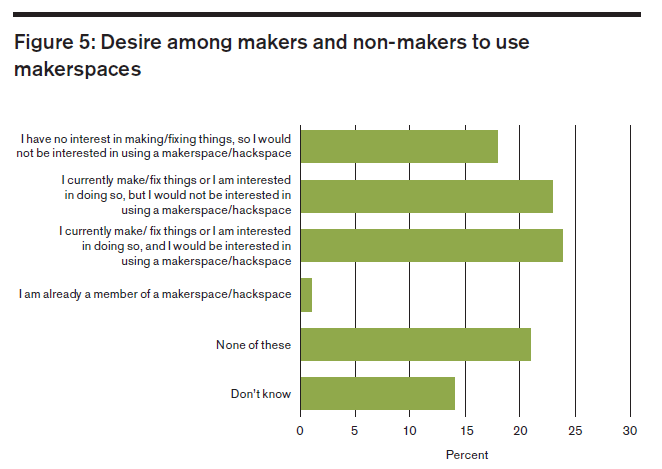

#7 – Nearly a quarter of people say there are interested in using a makerspace

An important question is whether makerspaces can attract more than the usual suspects. Are they just preaching to the converted, or can they encourage new and would-be makers to join their ranks? Promisingly, our survey with YouGov indicates a strong appetite among the population to get involved in making and to do so within communal workshops. Close to a quarter of people say they would be interested in using a makerspace, considerably more than the 1 percent who currently do so. Thanks to the digitisation of tools and the proliferation of online learning platforms, it is also becoming cheaper and easier to make objects of good quality.

#8 – Yet makerspaces face several dilemmas that may lead them astray from their founding values

The future is by no means certain for makerspaces. They face several challenges - particularly in the domains of governance, finance, membership and ethics – and many will be torn between pragmatic and idealistic poles as they seek to grapple with these. Should they seek external funding from corporate backers if it means sacrificing some of their independence? Can those that have a distributed model of governance continue to heavily involve members in decision-making without the organisation becoming dysfunctional? And how can makerspaces ensure their makers abide by high standards of ethics and sustainability, without being intrusive and interfering?

In partnership with our Fellows, the RSA hopes to explore these questions in more depth over the coming months.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.