Recently I saw a Facebook post of a woman who had been denied a credit card by her bank. Having declared a mental health condition, which she was successfully managing, the bank had at first increased the liable annual interest rate, and then questioned the suitability of her holding a credit card at all.

It seems that the gap between people living with or without mental health conditions extends beyond the likelihood of premature mortality. It is quietly endemic across a range of life experiences.

The Open Public Services Network (OPSN), based at the RSA, has been exploring some of these differences using publically available health and local authority data. Guided by an expert panel of mental health care information professionals and clinicians, OPSN has drawn together a number of disparate datasets that, whilst publically available, are only accessible if and where people know where to look.

Public sector transparency hinges on appropriate communication of data, not just releasing a complex dataset in an unknown corner of a website. It is the communication of data to the public that OPSN is concerned with, and this is the third of our major projects designed to improve access to comparative data in public services. In this way, we transform data from being a closed shop business, to a truly open means of shifting power to people and communities – informing service users of the facts, supporting them in their dialogue with providers, prompting wider public debate and holding to account commissioners, regulators and policy makers.

Funded by the Cabinet Office Data Release Fund, OPSN has created four new, composite indicators (with the datasets available for download under open license here). These indicators are designed to enable people, particularly patients, to answer four important questions:

- How well is my GP looking after my physical health needs?

- What is the likelihood of getting access to the right psychological therapies, and what is the impact if I don’t?

- Am I more or less likely than average to be prescribed anti-depressants?

- How well am I helped to live well with my condition?

We know that people with mental health conditions are more likely to die prematurely (before 75 years old). What’s new in the data we publish today is the extent to which this, and similar trends of excess mortality for people living with mental health issues, is underpinned by GPs failing to look after their physical health needs (question 1).

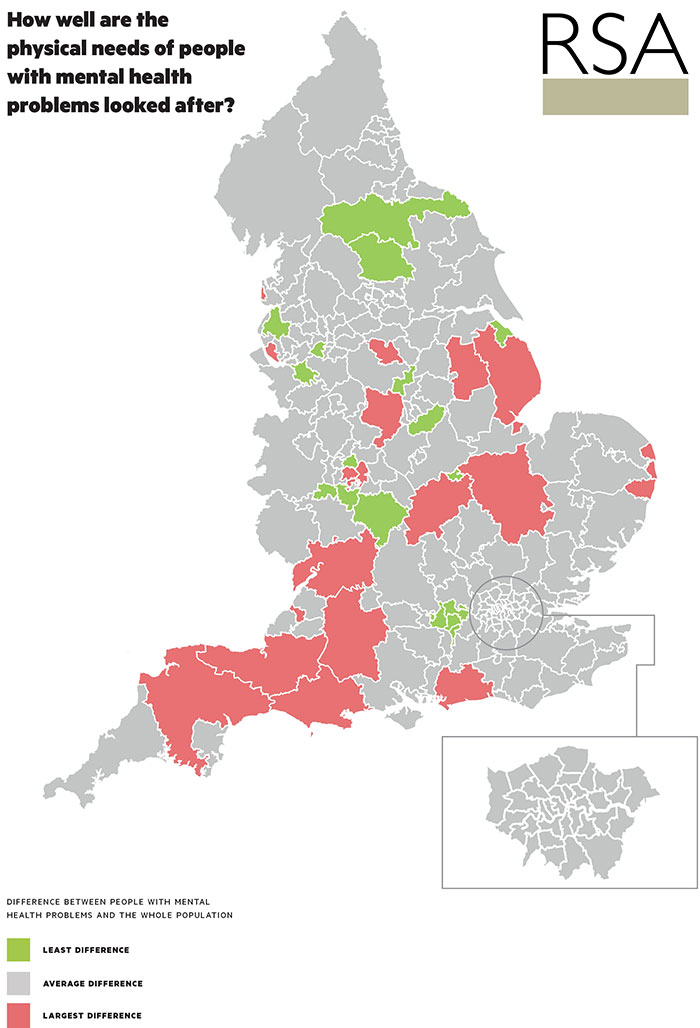

The map below illustrates shows that large areas of the South West, for example, experience the greater difference in the rates of referral for physical tests, including high cholesterol and diabetes. Leaving these often-treatable long-term physical conditions undiagnosed is a key risk factor in the overall health of local people. In our accompanying report, ‘Getting the Message on Mental Health’, we call for Public Health England, the Local Government Association and public heath leaders urgently to agree a systematic review of strategies to improve the physical as well as mental health care of people with mental ill health, and especially those with the most serious of conditions.

Maps of our other three composite indicators (see above) can be found here, illustrating the fact that in Sandwell, for example, people with serious mental health conditions are 50% less likely to be employed than the total population. In Surrey Heath, only 3.25% of the population with anxiety and depression have, in any one calendar month, access to the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme (IAPT). Croydon CCG does little better, with 4.33% accessing talking therapy treatment.

But if these variations were troubling enough, what’s clear in each of the illustrations above is the extent to which there are data deserts - where Clinical Commissioning Groups or Local Authorities are failing to collect sufficient or comparable aggregate (anonymised) information.

Lack of data is arguably the biggest indictment of our mental health system. Whilst there is a national minimum dataset and the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme reports its own access and outcomes data, what is available is mostly focused on secondary care hospital and community services. There is very little information on primary care services, where 80-90% of all those with mental ill health present for treatment. The Quality and Outcomes Framework for GPs (QoF) has removed several indicators for cardiovascular and diabetes checks in patients with severe mental illness for 2014/15, the seriousness of which is articulated by Dr David Shiers during our research: “This is of considerable concern given that people with severe mental illness die on average 15-20 years earlier than the general population, mainly from potentially preventable physical disorders. For example, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is 2-3 fold higher compared with the general population, and rates of undiagnosed diabetes are up to 70%.”

All this begs the question, how can we aspire for parity of esteem between mental and physical health if we cannot sufficiently understand the needs of local people or the degree to which our current configuration of services meets them? When up to one in four people will experience mental health problems in their lives at one point, we can’t continue to brush it under the proverbial carpet in primary care and hope that it is enough for other aspects of the health system to capture the complex causes and consequences of mental health.

Try our interactive tool: Living a Long Life? How mental health impacts life expectancy

Data: Download our data & methodology

Find out more about the OPSN Mental Health project

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Hi Charlotte,

Your blog raises a number of issues for me as I read.

Not only, in my view, do you refer to the real need for a fresh examination of how we view psychological health and wellbeing - you also highlight, in your credit card example, the punitive treatment of 'those who are different'.

In both cases RISK assessments rule! But what if the basic assumptions behind the risk assessment are flawed!

I believe your mapping highlights the symptoms of a society in 'psychological transition' that in many cases is led by those who both appear and think differently and we quickly seek to normalise, through medication or the restriction of freedom.

Since 1997 I have pursued an in depth appreciation and application of Integral Psychology which for example supports a reframe of every basic assumption of how we view all aspects of health. I was struck by your quote by Dr David Shiers - The litany of symptoms, which from my stance are all avoidable, paints a sorry picture.

You are right - there is a better way waiting to be grasped.

Well done.

It's scary stuff. I am slightly bias here but we can't brush issues like this under the carpet anymore.

This is truly excellent work and crosses over into the work are supporting around empowerment of individuals to be active participants in their own care and well being. The issue of vulnerability is also ever present in how consumers are being treated within financial services and there is a strong correlation between the insights here and the work done recently by FCA see https://vimeo.com/116958153 and the related report https://www.fca.org.uk/static/documents/research/vulnerability-exposed-research.pdf

The challenges of those mental health challenges getting the right level of support is greater than those with physical health issues but the two intertwined. There has also been some person centred work undertaken by organisations like action on depression to enable individuals to active participate in securing the support they need https://youtu.be/kekJ0T-JKso

Hi Charlotte,

I'm not 100% sure what the gist of this blog is, but my comment relates specifically to mental health and children (albeit it this case one on the cusp of 18).

I have an 18 year old son who is clinically diagnosed as Aspergers.

We as a family recently returned from Italy after 8 years as a result of my son not being able to integrate into a school system (the international IB in Italy).

After the whole family returned to the UK as a result of my elder son (he has a younger sibling) we attempted to settle into a normal 'life' in the UK.

To cut a long story short and to give an example of how the NHS is utterly failing young children (and I suppose also adults) let me tell you what happened to us in the last month.

My son had a breakdown and told his (private therapist -as an NHS one was 6 months away on a waiting list) that he wanted to commit suicide. As a care of duty she referred him to the NHS crisis group (whoever they may be).

We tried to contact them from the number we were given but only ever received a voicemail.

14 days later we were called by said group and, in an exasperated tone were asked how our son was. I turned to my wife and suggested that I tell them that he killed himself 9 days ago (given that when children say they are going to kill themselves data tends to suggests they either do it quickly or not at all), but resisted the temptation. On hearing that he was still alive and ok physically they hung up and we have not heard from them since.

I have to ask what is the point of this particular NHS 'crisis unit'? If our child were a serious case, he would be dead, and a phone call 9 nine days later is meaningless. Fortunately he was not a 'crisis' case, even though his therapist had flagged him as one.

This data is the start of a long journey. We have a system which is completely overwhelmed and under-funded, I see that every day in Croydon. I am not surprised to see blocks of missing data. The data needs to be analysed at ward, not borough level. Croydon has huge variations in life expectancy and wealth, which average out and mask significant problems. As property in Croydon is relatively cheap we house a very large number of people with mental health, alcohol and drug related problems sent here from surrounding boroughs - it is often a business and the "homes" and "hostels" are commercially run, many with low-paid, poorly trained staff. The UK is the European black spot for drug related schizophrenia problems.

Further, the presence of the Home Office in the Borough means that many recent arrivals into the UK stay here waiting to be processed; people that flee from War and oppression also bring with them their own mental health problems which are compounded by culture shock; and surviving, whilst they wait, in poor quality overcrowded accommodation.

Most of the "significant problems" are housed in a few wards; whilst other wards seem to be like another country.

Then competing for resources are our own home grown population struggling to get diagnosed or access help on a timely basis. My latest shocker was a client who when his family eventually got him help for anxiety were told by the Counsellor that his anxiety was not the type that their service dealt with; they only dealt with another type of anxiety.

Mental health is not just about the immediate services to address it; it is also about quality of housing; a person's sense of safety at all times, including when they sleep; access to a predictable and adequate income; quality of public spaces and parks; sport and physical development; and community.

It is difficult to see with the current "cuts" that there is any real political will to address any of these issues.