Peer-to-peer lending was supposed to be the future of retail banking. But a number of alleged scandals, encroaching institutional involvement and slowing transaction volumes have drawn a cloud over the sector. Should we be worried?

Peer-to-peer lending is the poster child for fintech – that wave of disruptive innovations currently sweeping through the banking industry. For those who aren’t familiar with it, P2P lending describes the activity of connecting individuals and businesses in need of a loan with lenders who can provide the necessary funds. The idea being to cut out the middlemen (ie the banks) and allow both parties to get a better deal. Think of it as finance for the people, by the people.

Beginning in 2005 with the launch of Zopa, the number of peer-to-peer lending platforms in the UK has since swelled to over twenty – among them Funding Circle (business lending), MarketInvoice (invoice trading) and LendInvest (real estate lending). According to research by Nesta and the University of Cambridge, transaction volumes – the amount of money flowing through P2P lending platforms – grew from less than £100m in 2011 to £2.9bn in 2015. The growth has been just as dramatic elsewhere, with China’s P2P market reaching nearly $100bn last year.

Little wonder that the industry has attracted so much attention. Investors have been lining up to get a piece of the P2P action, with seven major venture capital deals taking place in the UK last year alone. London, the crucible of fintech activity in Europe, can now boast of its first P2P lending unicorn – Funding Circle – which is valued at $1 billion. The sector has also won the admiration of several senior bankers, including Vikram Pandit (ex-Citigroup), John Mack (ex-Morgan Stanley) and Hans Morris (ex-Visa), all of who have invested in P2P platforms.

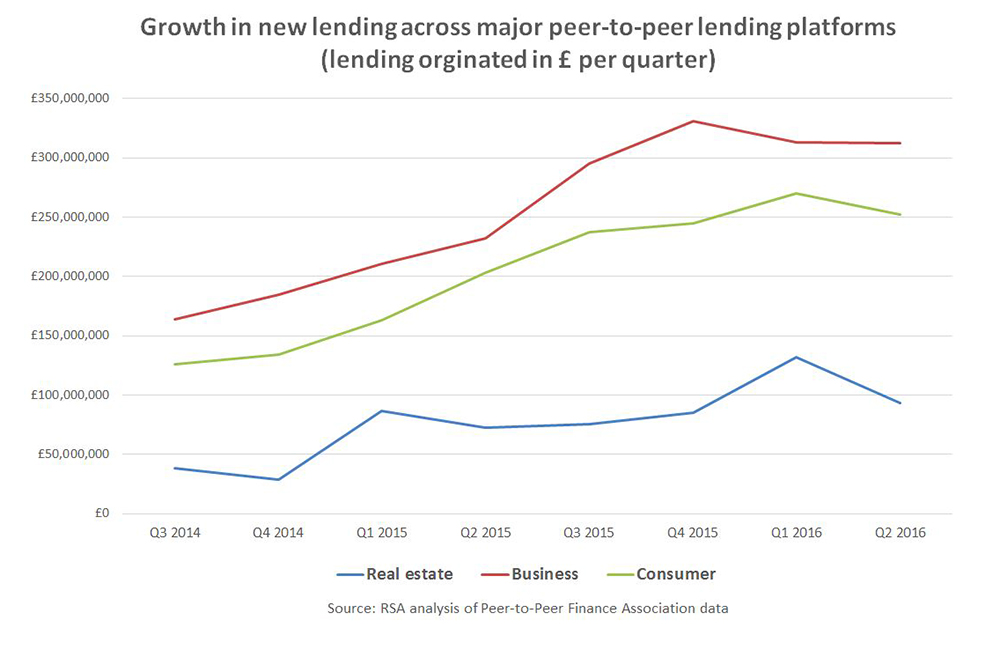

But is the hype warranted? A closer look at the state of the market raises a number of concerns – the first being that we may have already reached the pinnacle of peer-to-peer lending (‘peak P2P’). Recent analysis by the FT shows that the transaction volumes of the UK’s five largest P2P lenders saw a stratospheric rise from 2010 to the end of 2015, but have since began to stutter, falling and then plateauing over the past few months. This trend is broadly mirrored in our own analysis of data from the Peer-to-Peer Finance Association (see graph below).

Why is this a problem? Because unlike banks, which can make money on captive and repeat business in current accounts, credit cards and remortgages, P2P lenders need to continuously find and process new borrowers in order to earn commission. Should the sluggish times continue, the danger is that P2P lenders may soon be tempted to shoot for riskier borrowers in order to maintain their rate of growth. Remember that these platforms have investors of their own to placate and appease, many of whom will be pushing for decisive action to keep transaction volumes on an upward trajectory.

Which brings us onto the next concern: apart from one or two cases such as Zopa, we have little idea how P2P lending platforms will fair in a full credit cycle, when the economy sours and people and businesses begin to renege on debts. This is not a pessimistic view of the market; boom and busts are the reality of market economies, and it is important that every financial intermediary is prepared for the bad times as well as the good. Most P2P platforms have what they call ‘provision funds’ that can cover a small number of borrower defaults. However, some of these reservation pots are already close to depletion.

Then there is the growing phenomenon of institutional involvement. P2P is steadily becoming I2P as banks, hedge funds and pension funds push greater sums of money through lending platforms in a bid to connect with borrowers. US-based platform OnDeck, for example, has received millions of dollars from Goldman Sachs to channel through its marketplace. The reason this may be a problem is because traditional lenders could end up cherry-picking the best borrowers, leaving individual lenders with deals that yield lower returns. A broader worry is that institutionalisation could water down the competition that P2P lenders were supposed to inject into an oligopolistic industry.

Finally, there is the question of where the money flows to on these platforms. Nesta and Cambridge University’s research is unequivocal: peer-to-peer lending has helped many thousands of people and businesses access loans in the face of rejection from high street banks. Yet only 20 percent of borrowers using P2P consumer lending platforms are women, and only a quarter earn less than £25k (note that the median wage of workers in the UK is £27.5k). Although the makeup of borrowers using P2P platforms may simply reflect lending patterns across the financial industry, it challenges the theory that fintech innovations are inherently more inclusive.

The point of raising these red flags is not to pour cold water on the P2P lending phenomenon. Many of these platforms promise users a brilliant customer experience, faster decision making, more choice and – for some – better rates on loans then they can find elsewhere. Indeed, one of the greatest impacts P2P lenders have had is in changing the practices of long-standing incumbents. Take Wells Fargo, which recently launched a rapid turnaround system for small business loans, partly to match the responsiveness of P2P startups. These innovations should linger on even if P2P platforms fade away, and suggests the sector could catalyse positive transformation in financial services without needing to achieve a dominant position in the loans market.

No, this is not to dismiss the real achievements of P2P platforms. Rather, it is a plea to be pragmatic and realistic about what P2P lending – and all forms of fintech for that matter – can ultimately achieve without a more significant structural change in the nature of the financial industry. John Kay, in his brilliantly detailed new book Other People’s Money, rightly reminds us of the fundamental functions of finance: to enable people to save for the future, receive and send money, manage everyday risks, and borrow to invest in a real economy that truly creates value for others.

P2P platforms may help to bring parts of the financial industry back to its mores, but they are far from the silver bullet some portray them to be.

The RSA is working with Grant Thornton UK on a new project, Big Bang 2, which will explore the economic and social implications of new fintech innovations. We will be blogging about our findings over the coming months, with a view to publishing a final report in the Winter.

Related articles

-

Banks are nowhere near a Kodak moment (and maybe that’s a good thing)

Benedict Dellot

Barely a week passes without another news story predicting the demise of banks. But how much of this is fiction over fact?

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Thanks for the post. It was great to come across the data sets highlighted. I feel if we look at the current state from a market evolution perspective then you will see the current platform are the first movers in the marketplace. Their primary task is to educate the consumer of the need for P2P. The banks / traditional finance companies will naturally respond to this new kid on the block.

However, as time goes on new business models and technologies will emerge that will solve the problems identified by the first movers. This second mover advantage will help realise the dream more effectively simply because the experience of the first movers to learn from.

Look forward to other thoughts.