Brhmie Balaram looks back at some of the big moments in the sharing economy this year and what they signal for 2017.

At the very beginning of 2016, the RSA published a primer on the sharing economy. The aim was to make sense of the sharing economy’s transformation from a sector buoyed by local, grassroots-funded initiatives to one driven by global, venture-backed corporations.

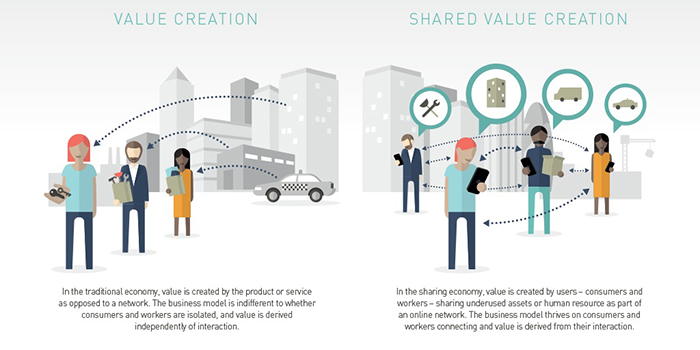

We were particularly interested in helping readers better understand the business model of ‘platforms’ like Uber and Airbnb, which underpin a new system of creating value. In traditional business models, value is created by selling a product or service, but in the sharing economy the value is created by users themselves – both consumers and workers – sharing their own assets and other resources with one another, connected by a platform.

This is an important point to grasp because it is also the root of the sector’s many troubles this year. If a platform is merely connecting users, rather than creating value itself, how much control can it exercise as an intermediary, particularly over those who are sharing their time and skills, or essentially, their labour? Should workers be given a greater stake in company profits considering their role in generating value? And what sort of responsibilities do intermediaries have to their users when problems arise on the platform?

Here are the big moments when these questions came into sharp focus.

A tug of war over workers’ rights

Those who ‘share’ their labour through a platform are classified as self-employed or independent contractors, which means that they likely have more autonomy over when they work, but are entitled to fewer rights. Two Uber drivers in London believed that the platform was exercising as much control as a traditional employer, however, and challenged Uber’s classification in an employment tribunal. The judges ruled in favour of the drivers, reclassifying them as ‘workers’ specifically, a little known third category that sits between self-employed and employed.

This ruling has significant implications for more than just Uber and its drivers, but also the sector at large. Other platforms are coming under greater scrutiny, most notably the food delivery company Deliveroo. Its couriers are currently demanding union recognition in Camden and look set to take similar legal action.

Uber is in the process of challenging the tribunal’s ruling, which was expected given the new costs it will incur if its drivers are classed as workers. However, they’re also moving full speed ahead with their ambitions to automate drivers, barely slowing down for regulators.

Co-operatives get competitive

While regulation tends to be a mere stumbling block for the likes of Uber, co-operatives may ultimately pose a more existential threat. Juno’s arrival on the scene in spring has particularly captured imaginations. Like Uber, Juno is a venture-backed ridesharing platform, but unlike Uber it offers drivers equity ownership. Juno’s founders have set aside a pool of restricted stock for drivers that they say is equal to their own shares; in practice, this means that the more fares a driver picks up, the more Juno shares she can earn. Rachel Holt, the Head of Uber’s North American operations, has admitted to keeping an eye on Juno’s journey.

While platform co-ops have yet to develop a strong presence in the UK, it seems inevitable from trends in the US that workers will want a greater share of the value that they themselves create.

The true colours of trust are revealed

Evidence of platform users acting on their racial biases first emerged in 2014 when Harvard professors Benjamin Edelman and Michael Luca noted discrimination against both black guests and hosts on the homesharing platform Airbnb. The profile photos Airbnb encouraged users to put up as a means of building trust backfired when it came to black users. The findings suggested that “there can be important unintended consequence[s] of a seemingly routing mechanism for building trust.”

When #Airbnbwhileblack started trending on Twitter this year, highlighting stories of racial discrimination on the platform, the company finally took action – more than two years after it was first alerted to the problem. Airbnb was hesitant to act in part because the responsibilities of platforms are still not clear-cut; as intermediaries, they are not yet held to the same standard as hotels and landlords, for example, in ensuring fair and equitable access to accommodation.

More money, more problems in 2017

There were some hiccups in growth in 2016; for example, Uber had to divest itself of its Chinese operations after haemorrhaging money trying to compete with its local equivalent, Didi Chuxing. Overall though, the company is experiencing fewer losses and enjoying boosts in revenue, as are most of the big players in the sharing economy.

Yet, even as these companies grow and begin to realise profits, they should not get too comfortable in the coming year. There will be more tussles in court, more challenges from worthy competitors, and more accountability demanded from those changing the way we work and live in modern times.

Likewise, those who have made gains against platforms must prepare for the fightback. These platforms are agile and have many friends – just last week, President-Elect Donald Trump appointed Uber CEO Travis Kalanick to his economic advisory team. Even more recently, Governor Doug Ducey welcomed Uber’s autonomous fleet of vehicles in Arizona after California clapped back against the platform for testing its self-driving cars on the roads without permits.

2017 will continue to be a turbulent time for the sharing economy for both platforms and their detractors.

Related articles

-

What is the gig economy?

Brhmie Balaram

The growth of Britain’s ‘gig economy’ has been profound. But what exactly do we mean by the gig economy?

-

Making the gig economy work for everyone

Brhmie Balaram

There are now an estimated 1.1 million people in Britain’s gig economy, which is nearly as many workers as in the National Health Service (NHS) England. Brhmie Balaram introduces our latest report into the gig economy.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.