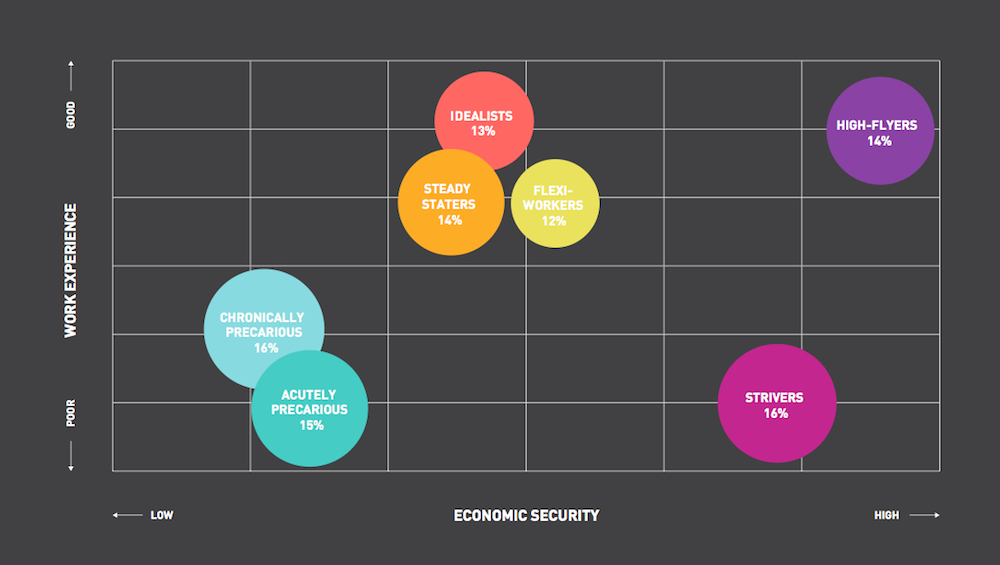

We set out to find out how workers are faring both in terms of their experiences of economic security and the quality of work in the UK. In the first report for the RSA’s new Future Work Centre, we reveal seven portraits of modern workers, reflecting on what it’s like to navigate today’s labour market.

The rise in zero-hour contracts and gig work has been followed by fears that the labour market is fragmenting into low paying, poorly protected jobs. The more flexible the workforce becomes, the more insecure workers appear to be, raising questions about whether workers’ interests are still being safeguarded under employment law.

In response to this unease, the government appointed Matthew Taylor to carry out a review of modern working practices. This was published in July 2017 and sought to achieve more than a reform of labour law for atypical workers. Its ultimate conclusion – that, as a society, we should strive for all work to be ‘good work’ – is relevant to workers across the labour market, no matter what the job. Our new report further explores the state of good work in the UK.

What we’ve found is that contract type and employment status are not adequate measures of whether someone is economically secure or in poor quality work.

For example, while some people in the gig economy may struggle to make ends meet as they go from job to job, others are satisfied with the hours they work and their degree of autonomy.

Moreover, there are many workers in seemingly secure jobs who are just managing to scrape by but are overlooked in debates about how to improve economic security when contract types or employment status are used as proxies for precarity. From retail workers to warehouse operatives, and from care workers to cleaners, we are beginning to uncover the hidden millions who are chronically broke year in, year out.

Our aggregate findings reveal that many workers have critical concerns.

When it comes to workers' financial circumstances:

- 26 percent of workers do not feel like they earn enough to maintain a decent standard of living.

- 34 percent, or a third of the workforce, would consider themselves to be ‘just about managing’.

- 43 percent do not have anyone in their household who they could depend on to support them financially in the event of hardship.

With regard to the quality of work, many report poor experiences.

- 28 percent of workers feel less secure in their jobs than they did five years ago

- 32 percent work excessive hours, and 47 percent often find work stressful.

- Only 40 percent of workers feel that they have good opportunities for career progression.

Our seven portraits reflect a more nuanced analysis of these issues, helping us to better understand who is having a good experience and who needs more support.

Overall, there are five key implications from our segmentation.

1. Conventional jobs are no panacea.

We identify more than a dozen indicators of economic security and quality work. So although, contract type and employment status are certainly factors in workers’ experiences, they are not proxies for security or precarity. When we confuse them for such we overlook the many workers in seemingly secure jobs who are struggling to get by.

2. Insecurity is both a personal and systemic phenomenon.

People’s feelings, perceptions and lived experiences matter alongside objective measures of economic security. This means that it’s possible for two people to be in the same kind of job and have completely different perspectives about economic security and quality of work. However, as personal as insecurity is, it is also influenced by systemic factors. For example, changes to welfare rules, public service provision, and educational opportunities can relieve or heighten insecurity. Wider forces such as globalisation and new technology may reassure some and aggravate others.

3. Shared challenges across segments betray common and pervasive problems in and beyond the labour market.

Although we may have seven distinct portraits of modern workers, there are shared challenges between them, driven in part by the systemic forces mentioned above. This is evident by the sheer number of workers who are having trouble making ends meet; can’t turn to others in the household for support; feel stressed out by their jobs; haven’t progressed in the last five years, and aren’t optimistic about future prospects. This reinforces the point that economic insecurity is more than just a labour market challenge and will likely need policies that extend beyond labour markets into areas such as asset ownership and new institutions for sharing risk and reward.

4. Different places and different sectors can have a significant bearing on experiences of work.

Places and sectors can shape people’s experiences of economic security and work, and the seven segments are distributed differently in different places and sectors. The implication is that it is worth pursuing place-based and sectoral approaches to raising the security and quality of work, which reflect the support needs of specific segments.

5. More flexibility shouldn’t mean less security.

Flexibility benefits both businesses and workers. However, in exchange for offering workers greater flexibility, businesses shouldn’t relinquish their sense of responsibility for ensuring that these workers are also able to maintain a decent living. Our own segmentation showed that some workers have both flexibility and security in work. To achieve this may mean that the obligations of businesses to workers will change, but we do not believe that overall they should be lessened.

No single reform will improve the economic security and employment experiences of British workers. We do not purport to be offering all of the necessary solutions and our suggested interventions, ranging from local enforcement of the minimum wage to personalised training accounts, are a starting point.

Download the report: Thriving, striving, or just about surviving? Seven portraits of economic security and modern work in the UK (PDF, 3MB)

Read online about the 7 portraits of modern work in the UK (on Medium)

Explore the 7 portraits through an online interactive tool

Related articles

-

A new machine age beckons and we are not remotely ready

Benedict Dellot Fabian Wallace-Stephens

We must push for an acceleration in the adoption of technology, but on terms that work for everyone.

-

Recruiting to Retention: The Emerging Role of Digital Credentials in the World of Work

Jonathan Finkelstein

An exemplar of a Future Work Initiative, Jonathan Finkelstein provides insights on how Credly are addressing the skills gap.

-

What does good work look like in the future – and how can we get there?

Benedict Dellot Fabian Wallace-Stephens

Today we launch the Future Work Centre and the Future Work Awards, two initiatives that will deepen our understanding of how policymakers, educators, employers and workers can and are preparing for the challenges of the 21st century.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

This highlights the blight of educated traditional middle income impoverishment economically and psychologically. One has to ask where has the money gone that was once there -inevitably tax is the answer though direct and indirect taxation and inflated cost of living in the UK. While we can be more innovative as a society, and business can share the benefits of hard won profits, this really is missing the the point about tackling the root of the problem, reducing wasteful government bureaucracy and a reduction in the tax burden.

Not to be confused wth cutting core and necessary services.

Essentially it is a sad fact that all efforts to protect low paid workers from exploitation is confounded. Industrial action only produced a 'union elite' who had power over their level of wages against the mass of non-unionised labour who did not. The national minimum wage has become essentially the only wage level for those who would have been near the bottom of the workforce pyramid. There is no longer the means for low paid workers to improve their prospects. The Blair government had the concept of a 'stakeholder society' where everyone would have a stake in what happened to their working and living environment in the UK. Some might say that this was just another politician's catchphrase. There must be a better way of organising society so that clear pathways to success can be discerned even by those on the lowest rung of the economic ladder. The latest tag is 'just about managing' groups in society and one can see how this might begin be addressed, but this is only tinkering on the periphery of the problem. I am interested in any conclusions this study group has drawn.

I don't wish to be cynical but most of this could be deduced by just looking around at modern UK society. What is far more important is how do we as society make constructive change, create fulfilling jobs, inspire the young to work harder to pursue careers which are not the soft option, create jobs which attract the less academic. I'm interested in solutions not endless social analysis.

Well, surely, this is about who makes key employment decisions and in whose interests. Globalisation in a free trade environment has meant that companies have been able to move production abroad where labour costs are lower; often importing the finished articles which are sold as British brands in the UK market place. This makes good business sense for them and their shareholders but leaves our labour market denuded of many of the jobs to which those 'just about surviving' would have aspired. We should have been using our muscle within the EU to insist that trade policy was for more modest growth in trade based on improved social conditions (and correspondingly higher costs) in the economies with which we traded.