Ten years ago, while Director of CentreForum, the liberal think tank, I wrote a paper calling on the Liberal Democrats to abandon their pledge to abolish university tuition fees. Within the party, the paper was as welcome as a turd in a swimming pool.

This was unsurprising. After all, the policy I was criticising was distinctive (both the other main parties were pro-fees), simple to explain and extremely popular.

And it was certainly doing a job for the party, particularly in battleground seats in university towns; seats like Bristol West, Oxford West & Abingdon, Cambridge and Sheffield Hallam. With the party’s opposition to fees on one side of each leaflet, and its opposition to the Iraq war on the other, the campaigns department had all the ammunition they needed in both Tory- and Labour-facing constituencies.

But there was a problem: the policy wasn’t just distinctive, easy to communicate and popular. It was also regressive, ineffective and unaffordable.

Regressive because replacing universities’ fee income with public spending involves a significant redistribution of resources from poor to rich, as non-graduates with relatively low life-time incomes are required to pay for the education of wealthier graduates through their taxes. Ineffective because it wasn’t high cost that was preventing low income school children from going to university, but low attainment, meaning the primary justification for the policy – that it would widen access – simply didn’t apply. And unaffordable because, at the very moment I was writing the paper, governments around the world were frantically bailing out the banks to prevent the collapse of the international financial system. The debts racked up by these bailouts (and by other palliative fiscal policies) ushered in a period of unavoidable austerity from which, a decade later, we are yet to emerge.

Knowing all this to be true, Nick Clegg, soon after being elected leader in 2007, tasked his HE spokesman, Stephen Williams, with formulating a new policy that accepted the principle of some private payment for university tuition. Williams’ task could not have been harder. Because of the party’s uniquely democratic policy-making processes, he first had to get a policy working group to agree an alternative policy. Then he had to get the members of the party’s internally elected Federal Policy Committee (some of whom had been elected on a ‘keep our fees policy’ ticket) to endorse it. Then he had to get the party conference to vote for it. Amazingly, he got two thirds of the way there. But ultimately, political considerations (internal as well as external) won out over policy considerations, and Clegg was persuaded not to put the issue to a vote on the grounds that he would lose if he did. He was thus condemned to fight the 2010 election on a flawed policy in which he didn’t believe.

He then made two mistakes, the first of which is easy to understand, the second less so. First, he agreed to sign the NUS pledge to “oppose any increase in fees” in the coming parliament – a difficult request to refuse when your party is committed to abolishing fees altogether. But then, amazingly, he decided to attack the other parties on the issue of ‘trust’, and to present himself to the electorate as a different kind of politician; a politician who would keep his promises. It was a decision that would come back to bite him hard.

Unfortunately, the lesson that has been learnt, both within and beyond the Liberal Democrats, is the wrong one: that Clegg’s real mistake was breaking, rather than making, the pledge.

…And now

Fast forward a decade and we’re back where we were when I wrote my 2008 paper: with an opposition leader with a realistic shot at power once again promising to abolish fees. There are two key differences between Jeremy Corbyn’s promise and Clegg’s, however. First, its cost has grown as fees have risen – from £2 billion to over £7.5 billion. And second, having seen what happened to Clegg, there is exactly zero chance of Corbyn repeating Clegg’s ‘mistake’. Should Labour win the next election on a promise to abolish fees, the policy, in all its awfulness, will have to be implemented.

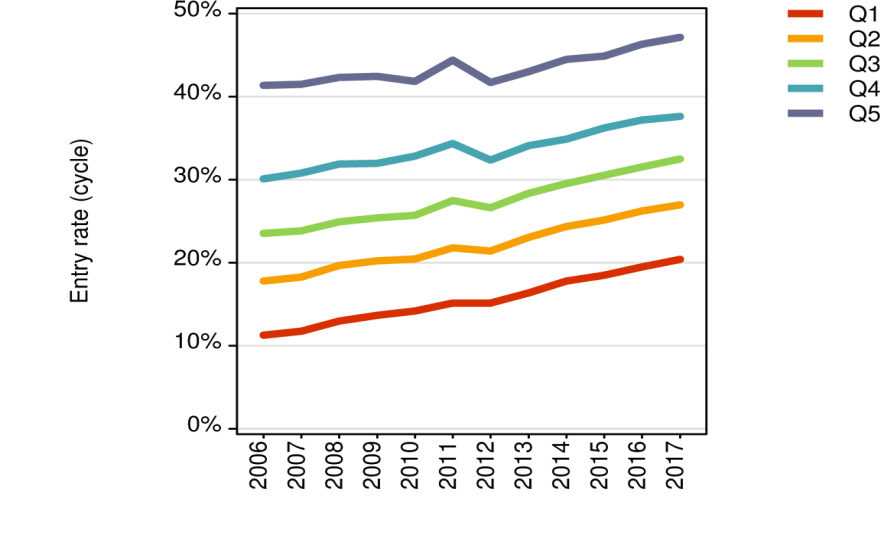

What hasn’t changed over the last ten years, however, is the fact that the current approach to funding university tuition – through fees, matched pound-for-pound by heavily subsidised income-contingent loans – has continued to succeed against its two key objectives: universities are on a sustainable financial footing and more young people are going to university than ever before. This continues a decades-long trend. Overall participation in higher education has increased from 3 per cent in 1950, to 8 per cent in 1970, 19 per cent in 1990, 33 per cent in 2000 and 49 per cent in 2017. What is more, this growth has benefitted students up and down the income scale. The participation rate of the most disadvantaged 20 per cent of students (the red line in the graph below) has grown by 78 per cent since 2006 and is now at its highest level ever.

18 year olds’ university entry rates by POLAR 3 quintile (an area-based measure of educational disadvantage), 2017

Of course income is not the only factor that explains differential university participation rates. As UCAS report, private school pupils are significantly more likely to attend university than state-educated pupils, females more likely than males, and members of ethnic minority groups more likely than members of the White ethnic group (who remain the least likely to enter HE).

The fact that these same inequalities are visible in GCSE and A Level attainment data should provide an important clue as to where the cause of the problem of unequal access is located and where we need to focus our efforts if we really want to address it.

To illustrate the point, the IFS looked at the HE participation rates of students of different socio-economic status but with the same A Level results to find out how much of the participation gap could be attributed to factors other than attainment (only one of which is debt aversion, the tiny nut that Mr Corbyn’s £7.5 billion sledgehammer is designed to crack). What they found is that when you control for prior attainment, the university participation gap almost entirely disappears. Which is why they conclude:

“The implication is that focusing policy interventions on encouraging disadvantaged pupils at age 18 years to apply to university is unlikely to have a major impact on reducing the raw socio-economic difference in university participation and in particular is not likely to increase participation by the lowest SES pupils markedly. Our results… suggest that there may be some gain from targeting lower SES pupils with good GCSE results but, again, this relatively late intervention is unlikely to result in a large increase in the HE participation rates of low SES pupils as compared with interventions to improve achievement at, say, age 11 years or earlier in primary school”.

Which is precisely why the Liberal Democrats invested every penny it would have cost to abolish tuition fees in the £2.5 billion Pupil Premium to reduce the attainment gap that opens up in early years and continues to widen throughout primary and secondary school.

And this is the real tragedy of Mr Corbyn’s policy. Because with the £7.5 billion he has earmarked for fee abolition, he could double the size of the Pupil Premium and still have enough money left over to ease the squeeze on school budgets and tackle the teacher recruitment and retention crisis.

It would be one thing if the only cost of implementing the policy was the opportunity cost. But the truth is it is likely to do actual harm, and to the very people it is supposed to help. Why? Because the lesson from around the world over recent decades is that when the full cost of university tuition falls on the Exchequer, student numbers need to be controlled and places rationed, and, when they are, it is the poorest students who find themselves locked out of the system.

Yet this is precisely what will happen if the politics of tuition fees are allowed to drive the policy making process. Which is why it is so important that the Review of post-18 education announced by Theresa May last week is properly insulated from those politics.

If it is, the review could seize the opportunity to tackle some real problems in the system.

The opportunity, for example, to address the market failure which sees students charged the same amount for low-cost-of-delivery, low-return courses as for high-cost-of-delivery, high-return courses.

The opportunity to look at why fees also don’t reflect variations in teaching quality, and whether the provision of better information to applicants is likely ever to solve that problem.

The opportunity to look at whether, despite all the protections built into the income-contingent loan system, there is a case for giving the poorest students the money they need to live off while they study, rather than lending it to them, so they don’t emerge from their studies carrying the biggest debts.

The opportunity to look at what lies behind the drop-off in the number of part-time students in recent years and what might be done to reverse it.

And the opportunity to look at the differences between the way academic and higher technical education are funded, and what might be done to reverse the staggering decline in the latter which, as review team member Professor Alison Wolf has shown, is now on the verge of collapse.

But with the Conservatives panicking about their woeful popularity ratings with young people, and Labour choosing to fight them over the cost of tuition, there is every reason to suspect that the review has been established for political, rather than policy, reasons. If so, the whole process could yet do more harm than good, though the quality of the members of the review team, and the constraints laid out in its terms of reference, provide reasons for optimism.

Overall, however, the lesson from last 20 years could not be clearer: when political imperatives and policy imperatives diverge – when the short term interests of politicians and the long term interests of the country are not in alignment – trouble follows.

When policy wins out, the politicians tend to bear the cost, as Clegg found out.

When the politics win out, the country bears the cost, as we all may soon find out.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Good piece. Three points;

1. When I last looked at this in detail some years ago, the graduate premium (the excess of lifetime income for graduates over non-graduates) as net present value was IRO £250k - reason enough, in terms of social equity, to end maintainance grants and free tuition (declaration of interest - I had both). So long as the cost to the 'consumer' of higher education is less than the graduate premium, this works. Why should building crafts, ag forest and fishing, mining quarrying engineering etc workers with steep earnings tail-off as physical strength / capacity falls pay Corbyn's proposed additional taxes to make graduates even better off than they are already, and make the wealth gap even wider than it is?

2. Higher education meams deferred gratification. Easier for someone from a comfortable middle class family with financial padding, resources and support behind them than young people from chaotic, struggling or disjointed backgrounds - the ability to complete HE courses lies not only with the students but the security and stability of the environment from which they are transitioning. And as you say, dealing with the primary and secondary attainment gap is vital if students from challenged backgrounds are to reach the starting line at all.

3. Agree wholly that the HE market is disfunctional and that there is no clear link between the cost of buying a higher education and the (lifetime) quality of the product delivered. Also the catastrophic collapse of what was once a superb technical / vocational HFE sector (declaration of interest - I trained as a Quarry Engineer many years ago at the Doncaster Metropilitan Intitute, a truly superb place staffed largely by highly qualified and experienced ex-NCB engineers and professionals, achieving institutional standards of excellence that my mid-90s London post-graduate university would simply not understand)

The need to re-engineer an HFE sector that is both fair and economically efficient has never been greater, and yes, we must divorce this totally from opportunist, short-term political in-fighting and recognise it as an issue of national interest.

This article is a real bean-counter’s extravaganza. The author does a brilliant job of looking at part of the evidence and ignoring the rest. He also spends half of the article explaining how tuition fees are inevitably a political issue and then goes on to make the political argument for why that should not be the case. A number of questions are left needing answers.

Are British universities attractive in world higher education terms, and, if they are, will they remain so? Current policies on tuition fees are predicated on the idea that demand is inelastic. I doubt it. Given the bloated size of fees in the UK, other countries’ universities look increasingly attractive - even to the more adventurous of the UK students.

Do British universities spend their income well and wisely? Often they do not. Look at the bloated bureaucracies, greedy vice-chancellors, rapacious senior management and uncontrolled building binges. Moreover, British universities have vigorously competitive internal markets, and the result is increasingly devastating.

Do other models not work? Models with low fees and no fees do work, in some cases rather well. I am not convinced by a vague, unsubstantiated reference to “the lesson from around the world”. In Britain, having educated, trained professionals is not considered to be a public good. Other countries are more enlightened. There is no inherent reason why control of access should exclude more of the poorest. This supposition merely makes a point - and a very political one - about WHO controls the access. In any case, we now have control of access on the basis of who can pay, and this is highly exclusionary.

Political decisions have resulted in British graduates facing a world in which houses are too expensive to buy, mortgages are hard to get, and immense debt blights their futures. In other western European countries this is not the case. It is hardly good for the advancement of the bottom rank of the social spectrum.

It is difficult to have policies without politics to guide them. What we need are politics and policies backed by good ethics. That does not necessarily mean neoliberal individualism. The article mentions the need “to address the market failure” of cartel pricing. Making higher education a better market will only blight it further. Students from poorer backgrounds are the casualties of the market approach, not the beneficiaries.