Andrew Pakes FRSA highlights a new poll commissioned by Prospect union and carried out by YouGov that shows there is growing unease about the ways in which bosses are keeping tabs on their employees as the work from home revolution gathers pace. He argues that employers must stop the spread of surveillance in our homes.

Over the last six months much of the developed world has experienced a transformation in how office workers do their jobs because of Covid-19. Many millions are working from home for some or all of the time. But for some, the change has come at a price, with unscrupulous bosses using the latest technology to snoop on their employees and monitor their online activities. Often this is done without the employee knowing about it. Polling shows that only a third (32%) of workers had even heard of keystroke monitoring and camera tracking technologies, while only a quarter (26%) had heard of electronic tracking with wearables.

We have already seen a steady stream of stories about companies using digital tech to monitor the work that workers do at home. Whether that is keystroke logging, software to gauge the attention of employees, or wearables to check where people are, a range of tools are now available to employers under the banner of ‘workforce analytics’. Some even promise to remind (and record) every time workers log onto certain websites like Facebook. And it is set to increase further.

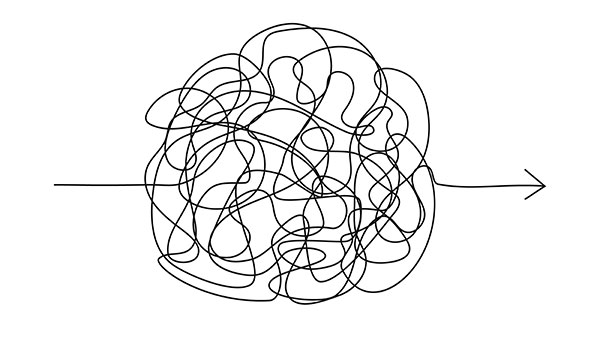

When these stories appear in the media, the outcry sometimes causes a rethink, but in other cases companies have ploughed anyway despite negative publicity. Undoubtably though, the public reporting of the use of this technology is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of how this tech is being used.

Ever since the term telecommuter was coined in the early 1970s, experts have long predicted a revolution in remote work. Up to now it had largely failed to materialise. The effect of a global pandemic and the availability of cheap and widely installed video conferencing – driven by the move to cloud computing as well as cameras on most devices –has meant that most white-collar workers will now have experienced remote work in one form or another.

And the signs are that, for at least a proportion of workers and companies, they actually prefer it. Workers, because it helps avoid long commutes or allows them to relocate away from cities and closer to friends and families. Companies, because it allows them to shrink costly real estate portfolios.

However, in the same way that the explosion of Facebook set the pre-conditions for the Cambridge Analytica scandal, if we are not careful, the explosion in home working could be establishing the preconditions for the wide and rapid roll-out of some unsavoury tech. If the future of work is going to be driven by data, we need to keep a close eye on what it means for workers. New research commissioned from YouGov by Prospect union is deeply worrying. It shows that nearly half of workers have not heard of these technologies at all.

And when we explained what the technologies were, two-thirds of workers were ‘somewhat’ or ‘very’ concerned about them being used in their homes. Three quarters (75%) of remote workers would be uncomfortable with keystroke monitoring with half (50%) very uncomfortable. More than four in five (85%) remote workers would be uncomfortable with camera monitoring at home with 70% very uncomfortable. A similar proportion (83%) of remote workers would be uncomfortable with electronic tracking with wearables, with 69% very uncomfortable.

Employers run the very real risk that by failing to engage with workers or their representatives and consulting on what they are doing they destroy the trust of their workforce. Trust is something that is very hard to rebuild once it is gone. The polling found that around half (48%) of workers said that they thought that introducing monitoring software would damage their relationship with their manager; this rose to 62% among younger workers (18-24yrs).

For unions this presents a real challenge. The technologies in use are simply too diverse to make blanket opposition an appropriate response. And indeed, what is appropriate in one context may be an entirely inappropriate intrusion in another.

Here are four areas we need to think about.

Firstly, we need to make much better use of existing rules, such as GDPR, to understand how workers data is being used, and to challenge where things are being done that are not in members interests. At Prospect we are getting tread to train union volunteers on how to use GDPR rules effectively, especially on Data Protection Impact Assessments when new uses of our data, such as monitoring technology, are introduced.

Secondly, we have got to start acting for collective data rights. Individual privacy is important, but when it comes to work, this technology is about workers’ rights. I’ve expanded on this theme for the Ada Lovelace Institute looking at the impact of the pandemic on collective data and work. As unions we need to organise around the use of data at work, in a similar way to how unions drove up physical safeguards through protection like health and safety. This means collective bargaining on data rights.

Thirdly, this is about wellbeing and the future of work. We need to challenge the tech industry to talk about the quality of jobs not just the quantity. The RSA’s Future of Work programme set a high standard here. Building on international examples, we should by negotiating for a British right to disconnect to take on the always-on culture and ensure remote working has acceptable boundaries.

Finally, unions must be generous in sharing with one another. This must include sharing internationally, as data increasingly flows across borders, and companies will use suppliers from across the world when introducing new workplace technology.

The ramifications of the Covid-19 pandemic are likely to be long-lasting and far-reaching for the world of work. Unions must make sure that when it comes to the use of new technology, workers can harness the benefits, without falling victim to ‘always on’ surveillance.

Andrew Pakes is Research Director at Prospect Union. He tweets at @andrew4mk

Related articles

-

Developing human friendly, social AI

Comment

Mark Lee FRSA

Mark Lee FRSA, argues for developing AI with human styles of thinking

-

Culture and accountability in banking

Comment

David T Llewellyn FRSA

David T Llewellyn FRSA writes on trust and confidence in banking.

-

Misinformation: educating the Google generation

Comment

Shelley Metcalfe FRSA

Shelley Metcalfe FRSA invites interested Fellows to participate in her research on teaching digital media literacy

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.